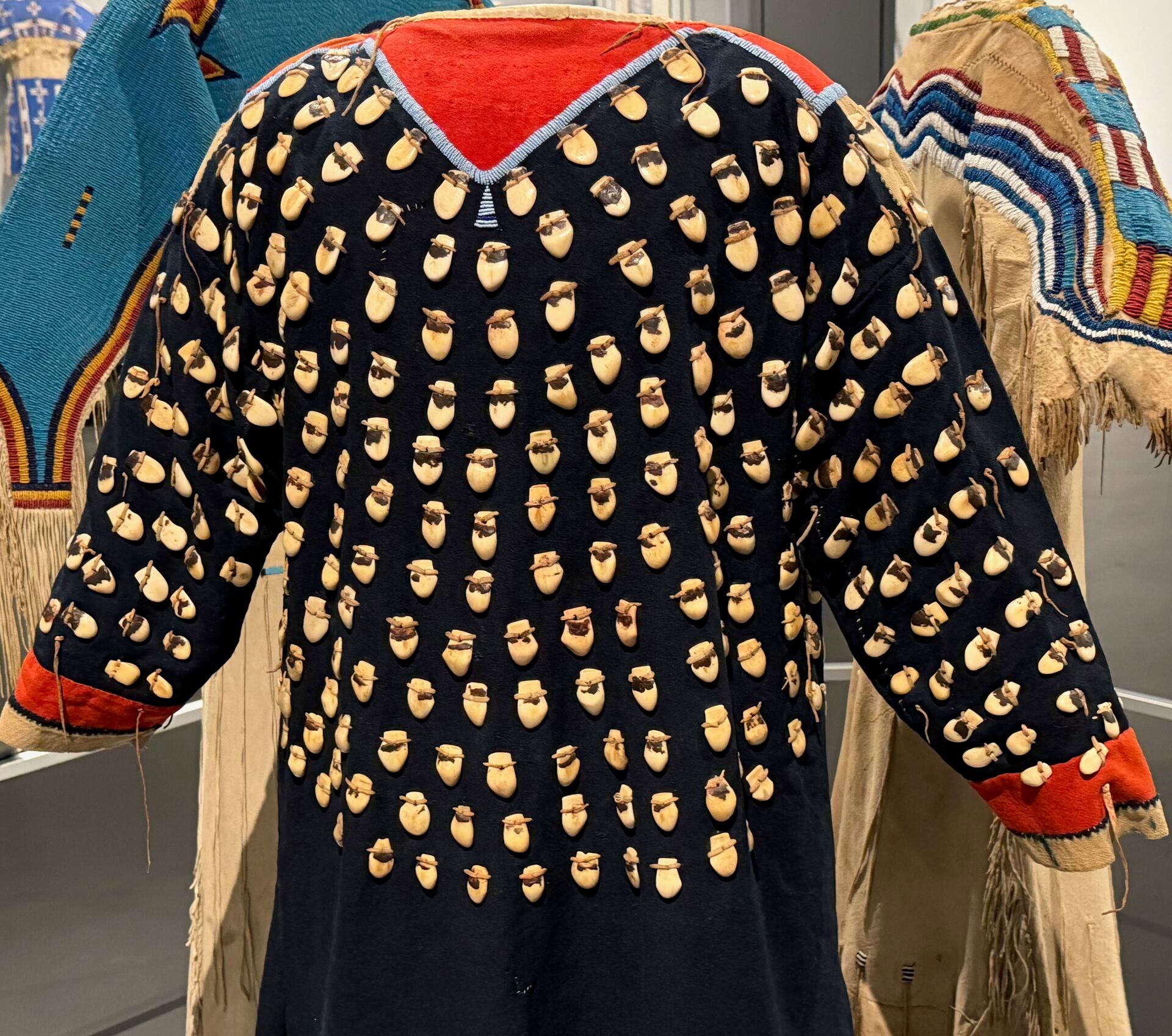

Dúusshile (Elk Tooth Dress) at the Autry Museum of Western Heritage in Griffith Park

On a visit to the Autry Museum of Western Heritage in LA, I saw this striking elk tooth dress, a symbol of Crow culture dating to around 1880.

Since an elk has only two ivories, or canine teeth, the numerous teeth on the dress show how skilled the hunter in the family was. The dress decoration, including the spacing and application of elk teeth, the contrasting fabrics near the neck and shoulders, and the ribbon work along the bottom, emphasizes its artistry.

The elk tooth dress also shows how well the women were provided for. Women have really kept us going; they were very resourceful and always found ways to carry on our culture.

The Two Sides of Technology

Most of us adults grew up without a lot of technology in our lives and then suddenly we now have all kinds of devices from computers and laptops to tablets and cellphones. Technology is everywhere and a big part of our daily lives. For many like myself technology has had a liberating effect, opening new doors for discovery and endless possibilities for new forms of creation and connection. Using technology was a choice we made, often before others were convinced the technology was worth investing the time and money. However, now we’re seeing the downside of ubiquitous technology in the lives of children.

Today, I wrote an article in Sebastopol Times on how the local high school district intends to remove cellphones from students for the entire school day next year. “They have a highly addictive device in their hands all day,” said the high school principal. For kids, it’s no longer a choice but a compulsion. It dominates their daily lives, making it harder for them to focus on the world around them and interact with real people face to face.

A few years ago, I might have disagreed with banning cell phones in the classroom, in part because I consider technology a liberating force. The more I see students today, however, it’s not about what they’re gaining by having cellphones; it is more about what they’re losing. They are distracted constantly by their phones; they hunch over and pull their hoodie tight over their head to be absorbed in their screens; they try to hide what they are doing; they get upset if they are drawn back and asked to pay attention to the physical world that surrounds them. Moreover, youth are losing their opportunity to develop the habits of mind that make us human. (See last week’s newsletter on Artful Intelligence.)

One of the things I’ve said about the maker movement is that we want people to see themselves as producers, not just consumers. We want them to see technology as tools for producing things that you dream of, things that nobody else could create. This is more important today than ever, and even more essential for our youth.

I have never thought that you learn to use the tools without someone showing you how to use them productively. That’s what mentors, coaches and others offer, offline or online. We see how other people do things and we learn from them. I’m convinced that the maker movement needs more people acting as mentors and coaches working with kids. We can help kids get control of the technology they use — recognizing that phones and social media are also a struggle for adults. Let’s empower kids to live and work on the good side of tech, allowing them to become better versions of themselves and live free without a screen addiction.

What do you want to make?

From “curious” to “doing”

Over the holidays, I took a four-day trip to Los Angeles. On a beautiful Sunday, my wife and I took an Uber to visit the Griffith Park observatory. I struck up an interesting conversation with our driver, Charldred, and I learned some things about LA that I didn’t know. I told him what I did and he was very interested and talked about his two kids. They had been to the Octavia Lab makerspace at the LA Public Library and the kids were fascinated by 3D printing. We exchanged contact information and when I got home I sent him a couple of the recent issues of Make:. I heard from Charldred this week:

I wanted to send a sincere thank you for the copies of Make: Magazine. My kids and I have been diving into them, and the impact has been immediate.

They were already interested in 3D printing, but after reading the magazines, they’ve gained a new level of confidence and are now eager to get into robotics. Seeing them move from "curious" to "doing" has been incredible.

We are definitely planning to be at both events this year—the one in April at the Central Library (Octavia Lab) and the annual Maker Faire. We want to make sure we are right there where the building is happening.

Thank you again for your great work and for inspiring the next generation of makers.

Alder Riley of Item Farm

In Make:V96, there’s an interview with Alder Riley, who has been developing 3D printing kiosks, first in a storefront in Vermont, then in malls in the Bay Area and now he’s putting them in schools throughout the US. I should add that Alder occupies a memorable place in my mind for his almost blind passion and dedication. He showed up one day in our then-SF office, probably in 2016. He had driven to the Bay Area from Vermont in a Prius with three 3D printers in the back. He also brought a mattress so he could sleep in the back of the Prius while he ran a mall kiosk on the peninsula. In this excerpt of the interview, Alder closed down his kiosk business and he was trying to figure out what to do next.

You had to figure out how to come back from that.

That’s a good way of putting it.

After the kiosk business shut down, I had a choice of going back to the East Coast with my tail between my legs, or I still had some 3D printers and I had found some friends who had warehouse space and I asked them: “Can I just live in your warehouse and print stuff for people?” That is what I did for the next three years. I refused to give up. I got very good at heating up burritos or hot pockets on the heated beds of a Flashforge.

The feeling I had at a Maker Faire where you are seeing the joy in people’s eyes when they have that sense of — wow, this technology is like magic. I have the desire to make that more common.

Alright, so what’s next?

That brings us to 2020. I was living and working in a warehouse and figuring out how to catch my big break. I went to startup pitch meetings and took advantage of their free sandwich platters while I was trying to pitch a company. I’m stuffing gyros and stuff into my pockets.

During the Covid, I got involved with the PPE efforts with the Helpful Engineering folks. I knew how to work with 3D printers. I knew how to juggle supplies, moving them back and forth. We were moving thousands of pounds of material across the country and negotiating with everyone.

I’ve got this just incredibly clear memory of driving down El Camino Real in Palo Alto and seeing hospital workers in the Safeway parking lot with signs saying “Can you make us masks or face shields? Anything helps.” Literally this is right next to Stanford and they’re begging for anything they can get.

I’d show up at the Menlo Park Library in the parking lot. I’d open up the back seat and the trunk, and hand out masks and face shields. Get as many as you want, I told them.

After Covid, when does Item Farm start?

Item farming, in case you didn’t know, is a term from video games where you're essentially in an area where random items spawn naturally as part of the balancing of the in-game economy. So you just sit there and you item farm. It’s this natural resource of almost infinite items. Item Farm was inspired by our PPE efforts, which introduced us to a lot of communities around the globe that had no way of making things, no local factories, no nothing.

What if there’s a microfactory, something like the size of a vending machine. Something that can be essentially shipped anywhere on the planet that would allow making things anywhere.

Given the frustrations that our team had with desktop 3D printers, we designed our own machine that’s a little microfactory where you could be making things for your community. It’s a one-stop shop instead of setting up a bunch of desktop 3D printers in a room.

So the Orchard system is a microfactory, essentially, six or eight 3D printer stations connected together.

An Orchard system is essentially a motor control system; it has 56 motor controllers spread across 14 ports, that we call “Branches”. Each branch can hold a module that does a manufacturing process like 3D printing, milling, plastic recycling, etc. This is how you have one machine that can have multiple manufacturing processes all working at the same time

I went with a bed slinger setup for our first 3D printing module because I wanted to maximize the visibility of the creation process.

A bed slinger? I don’t know what that means.

Just moving the bed around in the y-axis. Our build areas are tilted at a 15-degree angle on a cantilevered arm. Because essentially you want to maximize the visibility of the build process. Kids can see it much easier and it doesn’t impact the build quality at all but it improves the experience. Most folks see our units as giant, multi-armed 3D printers.

Do you still have the intention to go into malls with Orchard and have more kiosks?

We still have the footprint that fits a standard kiosk, but our main customers are schools and places like Boys and Girls Clubs and YMCA’s. Our first customer is a retailer that was essentially a kids’ art studio; it’s this model where you have canvases or clay things that are prefabbed. Then the kids come in and they paint them. You can paint with PLA all day long. We set up an Orchard there and they are printing things that the kids designed and then the kids would paint things that they had designed.

Make Things is a weekly newsletter for the Maker community from Make:. This newsletter lives on the web at makethings.make.co

I’d love to hear from you if you have ideas, projects or news items about the maker community. Email me - [email protected].